Source (GitHub) | Download notebook

6.3. Using TensorBoard in TensorFlow 2 on the IPU

TensorBoard is a visualization tool provided with TensorFlow that provides a platform to view many aspects of model training and inference at near real-time intervals (if so configured). Data that may be visualized includes, but is not limited to:

Training losses and metrics

Images

Model graphs

Histograms/distributions of variables (such as model parameters, hyperparameters, etc.)

In fact, the data that may be displayed in TensorBoard is entirely customizable by the use of custom callbacks (as we will see later in this tutorial). IPU TensorFlow works with TensorBoard out of the box!

In this tutorial, we shall develop a very simple convolutional network to train on the MNIST dataset for character recognition. This problem is purposely selected for demonstration as it is rather straightforward and allows the focus of this tutorial to be on the use of TensorBoard.

Preliminary Setup

To run the code in this tutorial there are two basic requirements.

A Poplar SDK environment enabled, with the Graphcore port of TensorFlow 2 installed (see the Getting Started guide for your IPU system)

Python packages installed with

python -m pip install -r requirements.txt

If you wish to follow along with the Jupyter notebook provided for this tutorial, then some additional setup steps are required.

First, ensuring that you have a Poplar SDK environment enabled, install the Jupyter Notebook server in that environment, as follows.

python -m pip install jupyter

Once the Jupyter Notebook server is installed in your environment, start Jupyter as follows.

jupyter-notebook --no-browser --port 8888

On your local machine, you can now forward the port 8888 (chosen here) to the remote machine running your Poplar environment. Note that the choice of port is entirely up to you. Here, 8888 is simply an example.

ssh -NL 8888:localhost:8888 <your-username>@<your-machine>.<your-domain>

You can now navigate in your web browser to the Jupyter instance running on

your remote machine via the address localhost:8888.

For more details about this process, or if you need troubleshooting, see our guide on using IPUs from Jupyter notebooks.

Introduction to TensorBoard and Data Logging

How does TensorBoard work?

TensorBoard itself runs independently of any TensorFlow processes, so starting and stopping TensorBoard does not affect any TensorFlow processes that may be running. The reason that TensorBoard and TensorFlow are independent in this way is due to the method of data transfer between them. Rather than a client/server model as one might first expect, there is no direct communication between the two packages.

Instead, TensorBoard monitors a log directory to which your TensorFlow program writes data in a format that is parsable to TensorBoard. So, getting TensorBoard running and ready to start displaying data from your TensorFlow program is as simple as just starting the Daemon.

How do I launch TensorBoard?

If we go ahead and enter tensorboard into a terminal (on a machine that has a

TensorFlow installation and tensorboard on your path), you will notice the

following error.

Error: A logdir or db must be specified. For example `tensorboard --logdir mylogdir` or `tensorboard --db sqlite:~/.tensorboard.db`. Run `tensorboard --helpful` for details and examples.

As we can see, TensorBoard will not start without a log directory (or, alternatively a SQLite DB) being provided.

For the purpose of this tutorial, we shall be using the

/tmp/tensorboard_example_logs directory as our log directory. Let’s go ahead

and launch TensorBoard.

tensorboard --logdir /tmp/tensorboard_example_logs

If all is well, then you should see output akin to the following on your terminal.

TensorBoard 2.7.0 at http://<your-machine>.<your-domain>:6006/ (Press CTRL+C to quit)

If you navigate to the address given in your terminal (in a browser of your choice), you should see the blank (no logged data) TensorBoard interface.

TensorBoard on a Remote Machine

If you use a remote machine for your TensorFlow development, then there are a couple of options for accessing TensorBoard remotely.

SSH Tunnelling

The first (and more secure) approach is to setup an SSH tunnel to your remote

machine, binding the remote TensorBoard port to a local port on your machine.

For example, to setup a tunnel that binds the TensorBoard port 6006 to port

6006 on your local machine, you would execute the following (on your local

machine).

ssh -L 6006:localhost:6006 <your-username>@<your-server>

In this example, navigating with your web browser to localhost:6006 should

yield the screen shown above.

Exposing TensorBoard to the Network

Alternatively, if you are on a secure network, you may start TensorBoard with

the --bind_all argument, which will allow access on the port used (6006 in

this example) from within the machines subnet.

Automatically Handling Log Directory Cleansing

When developing a TensorFlow program it may sometimes be desirable to clear the

current data displayed by TensorBoard and start fresh. Below is a simple

function to handle this clean-up for us. The function

create_tensorboard_log_dir first checks that we have access to the /tmp

directory (recall, for this tutorial we are using the log directory

/tmp/tensorboard_example_logs), then it deletes the old log directory (if it

exists) and (re)creates the log directory.

import os

import shutil

def create_tensorboard_log_dir():

"""Handles deletion and creation of the TensorBoard log directory."""

# Ensure we have the top level /tmp directory first.

path = "/tmp"

if not os.path.isdir(path):

raise RuntimeError(

f"Unable to locate {path} directory. Are you running on a Unix-like OS?"

)

# Delete the log directory, if it exists.

path += "/tensorboard_example_logs"

if os.path.isdir(path):

try:

shutil.rmtree(path)

except OSError as e:

print(f"Unable to remove {e.filename} due to: {e.strerror}")

# Create the log directory.

try:

os.mkdir(path)

except OSError as e:

print(f"Unable to create {e.filename} due to: {e.strerror}")

return path

Logging Data with tf.keras.callbacks.Callback

When using a tf.keras.Model or tf.keras.Sequential model (as we have above)

we have access to three main APIs: fit, evaluate and predict. These APIs

take an optional callbacks parameter, which is a list of

tf.keras.callbacks.Callback instances to be executed on the occurrence of

certain events, such as the end of a training epoch.

Continuing on with the development of our example, we shall define a simple

tf.keras.callbacks.Callback derived class to provide simple staggered

execution functionality.

import tensorflow as tf

class StaggeredCallback(tf.keras.callbacks.Callback):

"""A simple `tf.keras.callbacks.Callback` derived class that

provides a check to allow staggered execution every `period` batches.

Args:

period (int): The number of iterations that should elapse before

`StaggeredCallback.should_run` returns `True`.

"""

def __init__(self, period):

self._period = period

self._n = 1

def should_run(self):

self._n += 1

return (self._n - 1) % self._period == 0

Note that the above class (StaggeredCallback) will not actually perform any

actions on any events as we have not overridden any event handlers. The

tf.keras.callbacks.Callback class provides the following event handlers to be

overridden.

on_train_begin(self, logs=None)on_train_end(self, logs=None)on_test_begin(self, logs=None)on_test_end(self, logs=None)on_train_batch_begin(self, batch, logs=None)on_train_batch_end(self, batch, logs=None)on_epoch_begin(self, epoch, logs=None)on_epoch_end(self, epoch, logs=None)

Running Evaluation at the end of an Epoch

We shall now write a simple callback to perform a full evaluation every $n$

training epochs. As we wish to perform an action at the end of an epoch, we

shall override the on_epoch_end handler.

class EvaluateCallback(StaggeredCallback):

"""Runs an evaluation pass on the provided test dataset.

Args:

path (str): The directory to which evaluation logs will be written.

model (tf.keras.Model): The Model on which to run evaluation.

pred_dataset (tf.Dataset): A Dataset to use for prediction.

period (int): The number of epochs to elapse before evaluating.

steps (int): The number of steps to perform evaluation in.

"""

def __init__(self, path, model, pred_dataset, period, steps=128):

super().__init__(period)

self._model = model

self._ds = pred_dataset

self._writer = tf.summary.create_file_writer(path)

self._steps = steps

def on_epoch_end(self, epoch, logs=None):

if not self.should_run():

return

res = self._model.evaluate(self._ds, steps=self._steps, return_dict=True)

with self._writer.as_default():

for k, v in res.items():

tf.summary.scalar(f"evaluation_{k}", v, step=self._n)

If we first turn our attention to __init__, you will see that

PredictionCallback takes the following initialization arguments.

pathThe TensorBoard log path.

modelThe

tf.keras.Modelinstance on which we will run prediction.

pred_datasetThe

tf.Datasetinstance on which we will run prediction.

periodThe period in epochs to run a prediction pass.

stepsThe number of steps in which to evaluate. Simply passed to

Model.evaluate.

The first thing to note is that EvaluateCallback derives from

StaggeredCallback (defined above), so we initialize the superclass with the

period at which the callback should perform an action. Thus, upon entry to

on_epoch_end, a check is made to determine if further execution should be

skipped (until reaching a number of epochs that is multiple of the period

parameter

The second important thing to note is the initialization of self._writer.

Here we are initializing a TensorFlow summary (tf.summary) file writer on the

TensorBoard log path. At this point, it is pertinent to introduce TensorFlow

summary ops (tf.summary) as the functionality provided is used extensively

when writing custom code to output data to TensorBoard. Within tf.summary are

many ops that are used to log out various types of data when invoked within the

context of a tf.summary.SummaryWriter (self._writer in our example).

With this in mind, we can turn our attention to the usage of res, the return

value of our call to self._model.evaluate (note the keyword argument

return_dict=True). Within the context of self._writer.as_default() we

iterate over each of the specified losses and metrics and write them out as

scalar data (note the call to tf.summary.scalar). This logged data is then

available within the TensorBoard log directory for the running TensorBoard

instance to display.

Supported Data Types in tf.summary

Within tf.summary there are many ops supporting a variety of data types that

can be logged, including the following.

generic(tensor summary)scalarhistogramimageaudiograph

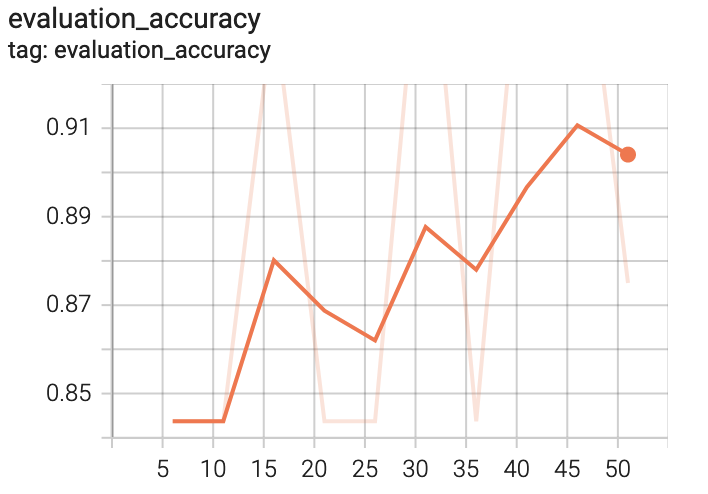

Logging Custom Image Data at the end of an Epoch

Now that we have seen how to build a basic tf.keras.callbacks.Callback

derived class to run an evaluation pass at the end of every $n^{th}$ epoch, we

may move on to build an example of logging out image data. As we will be

training and analyzing a Convolutional Neural Network (as defined in

create_model), we will in this section be building a callback to render out

the filters of our convolution layers. The end result for a given convolution

layer (conv_1 in the example image that follows) should look something like this.

As with our implementation of EvaluateCallback, FilterRenderCallback shall

also derive from our StaggeredCallback class to allow for the limiting of

rendering to be every $n^{th}$ epoch. The implementation of

FilterRenderCallback is as follows.

import itertools

import math

class FilterRenderCallback(StaggeredCallback):

"""A `StaggeredCallback` derived class that renders the kernels of a

given list of convolution layers.

Args:

path (string): The directory to which rendered filters will be written.

model (tf.keras.Model): The Model from which to extract filters.

layer_names (list(str)): A list of layer names from which filters should

be extracted and rendered.

period (int): The number of epochs to elapse before rendering filters.

"""

def __init__(self, path, model, layer_names, period):

super().__init__(period)

self._model = model

self._layer_names = layer_names

self._writer = tf.summary.create_file_writer(path)

def tile_filters(self, filters, name, step):

# First normalize the filters.

fmin = tf.reduce_min(filters)

fmax = tf.reduce_max(filters)

filters_norm = (filters - fmin) / (fmax - fmin)

# Instead of providing each filter as a separate image to summary_ops.image

# we here collapse the leading dimensions to yield a (D, D, N) tensor,

# where D is the filter size and N the total number of filters.

shape = (

filters_norm.shape[0],

filters_norm.shape[1],

filters_norm.shape[2] * filters_norm.shape[3],

)

filters_collapsed = tf.reshape(filters_norm, shape)

# Split into a list of N DxD filters.

filters_split = tf.experimental.numpy.dsplit(

filters_collapsed, filters_collapsed.shape[-1]

)

# Find the width and height of the resulting image, not in pixels but

# in the number of filters to display in each dimension.

WH = int(math.sqrt(len(filters_split)))

# Generate each row of the output image.

filter_num = 0

rows = []

for _ in range(WH):

# Collect the filters for this row.

row_images = [

tf.squeeze(t) for t in filters_split[filter_num : filter_num + WH]

]

# Generate vertical padding to be used between filters.

col_padding = [tf.zeros((filters.shape[0], 1))] * WH

# Interleave filters and padding.

row = list(itertools.chain(*zip(row_images, col_padding)))

# Stack, excluding the last padding tensor as there is no filter

# to the right of it.

rows.append(tf.experimental.numpy.hstack(row[:-1]))

filter_num += WH

# Find the width of the image.

W = rows[-1].shape[1]

# Generate horizontal padding.

row_padding = [tf.zeros((1, W))] * WH

padded_rows = list(itertools.chain(*zip(rows, row_padding)))

# Stack and expand dims.

img = tf.experimental.numpy.vstack(padded_rows[:-1])

img = tf.expand_dims(tf.expand_dims(img, -1), 0)

# Write out the resultant image.

with self._writer.as_default():

tf.summary.image(name, img, step=step)

def on_epoch_end(self, epoch, logs=None):

if not self.should_run():

return

for layer_name in self._layer_names:

filters = self._model.get_layer(layer_name).get_weights()[0]

self.tile_filters(filters, layer_name, epoch)

It can be seen that the __init__ implementation of FilterRenderCallback is

rather similar to that of EvaluateCallback; we take a path to write data to,

a model to extract filter weights from, a list of layer names from which these

weights will be extracted and finally a period at which to produce a new

rendering.

Notice that the implementation of the event handling method on_epoch_end is

rather lightweight. It first checks if the computation should be skipped for

the current epoch (as per the specified period), akin to EvaluateCallback.

Then, for each specified layer (the list of names passed to __init__) we

extract the kernel weights for that convolutional layer and pass them with the

layer name to the tile_filters method which, as the name suggests tiles the

convolution filters to be rendered as the image you see above.

Take a moment to familiarise yourself with the logic in tile_filters if you

are interested, however the majority of the method is not essential to

demonstrate the use of TensorBoard and tf.summary.image. Most of it is just

to generate a pretty picture, so that we have something to log for TensorBoard

to display.

The crucial part to note is the following two lines.

with self._writer.as_default():

tf.summary.image(name, img, step=step)

Notice that the process for logging image data is near identical to the

tf.summary.scalar case in EvaluateCallback.on_epoch_end.

Using tf.keras.callbacks.TensorBoard

Now that we have seen how tf.keras.callbacks.Callback works and how we can

derive from it to define our own custom callbacks, we shall have a brief look

at tf.keras.callbacks.TensorBoard, which is a built in callback to allow

monitoring of basic information such as losses, metrics, parameter

distributions and our model graph with minimal setup required.

An impressive amount of information is available to us from simply creating an

instance of tf.keras.callbacks.TensorBoard and passing it in the callback

list to a Keras model. We shall see in a later section, once we have started

training our model the information generated by this callback.

Model Setup & Data Preparation

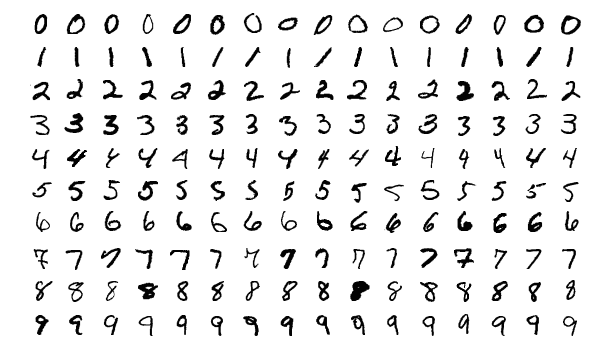

For the example we shall develop in this tutorial, we wish to obtain three

MNIST datasets; training, validation and test datasets are extracted from

tf.keras.datasets.mnist. Below we define a function create_datasets that

loads the Keras MNIST dataset and processes it for our purpose here. The first

step is to split the MNIST training set into both training and validation sets,

as only two sets are provided (train and test) whereas here we require

training, validation and test datasets.

Following this split, the data is normalized, shuffled and placed into a

tf.data.Dataset. The last preprocessing step is to cast the data to

tf.float32 and convert the targets (class labels) to tf.int32 one-hot

encodings.

import numpy as np

def create_datasets(train_validate_split=0.8, num_to_prefetch=16):

"""Create datasets for training, validation and evaluation.

Args:

train_validate_split (float): The proportion of data to use for training

versus evaluation.

num_to_prefetch (int): The number of dataset elements that

should be prefetched.

Returns:

tuple(tf.Dataset): Training, validation and testing datasets.

"""

def prepare_ds(x, y):

# Normalize.

x = np.expand_dims(x, -1) / 255.0

# Shuffle and batch.

ds = (

tf.data.Dataset.from_tensor_slices((x, y))

.shuffle(10000)

.batch(32, drop_remainder=True)

)

# Cast and convert targets to one-hot representation.

ds = ds.map(

lambda d, l: (tf.cast(d, tf.float32), tf.cast(tf.one_hot(l, 10), tf.int32))

)

return ds

# Load MNIST dataset. The training set is split into training and

# validation sets.

mnist = tf.keras.datasets.mnist

(x_train, y_train), (x_test, y_test) = mnist.load_data()

N = int(train_validate_split * x_train.shape[0])

# Get the datasets.

training_ds = prepare_ds(x_train[:N], y_train[:N])

validation_ds = prepare_ds(x_train[N:], y_train[N:])

test_ds = prepare_ds(x_test, y_test)

# Repeat (for training), prefetch and return.

return (

training_ds.repeat().prefetch(num_to_prefetch),

validation_ds.prefetch(num_to_prefetch),

test_ds.prefetch(num_to_prefetch),

)

The datasets generated by create_datasets consist of $(28 \times 28)$

greyscale images of handwritten numerical digits and their associated value

as a target, $[0, 1 \dots 9]$

So, we see that we have a very straightforward classification problem.

Model Definition

As MNIST classification is a reasonably trivial task, only a modest complexity

model is required. The function that follows (create_model) will generate a

tf.keras.Sequential instance with the following layers. Note that the IPU

pipeline stage assignment does not occur until a later stage, it is merely

documented here for reference.

Layer Type |

Pipeline Stage |

|---|---|

28x28x1 Input |

N/A |

32 Filter, 3x3 Convolution |

0 |

2x2 Max Pooling |

0 |

64 Filter, 3x3 Convolution |

0 |

2x2 Max Pooling |

0 |

32 Filter, 3x3 Convolution |

1 |

2x2 Max Pooling |

1 |

Flatten |

1 |

Dropout (0.5 probability) |

1 |

10 Unit Dense with Softmax |

1 |

def create_model():

"""Create a simple CNN to be split into two pipeline stages."""

return tf.keras.Sequential(

[

# Input layers do not get assigned an IPU pipeline stage.

tf.keras.layers.Input((28, 28, 1)),

# Pipeline stage 0.

tf.keras.layers.Conv2D(

32, kernel_size=(3, 3), activation="relu", name="conv_0"

),

tf.keras.layers.MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2, 2), name="pool_0"),

tf.keras.layers.Conv2D(

64, kernel_size=(3, 3), activation="relu", name="conv_1"

),

tf.keras.layers.MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2, 2), name="pool_1"),

# Pipeline stage 1.

tf.keras.layers.Conv2D(

32, kernel_size=(3, 3), activation="relu", name="conv_2"

),

tf.keras.layers.MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2, 2), name="pool_2"),

tf.keras.layers.Flatten(),

tf.keras.layers.Dropout(0.5),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(10, activation="softmax"),

]

)

Model Training

We shall now proceed to build and train our model so that we have some data to view in TensorBoard. As a recap, we have so far implemented the following “ingredients” of our example TensorFlow program.

create_datasetsA function to load the MNIST dataset and provide us with three splits of data for training, validation and testing.

create_modelA function to provide us with our Convolutional Neural Network with a 10 class classifier (an instance of

tf.keras.Sequential.

create_tensorboard_log_dirA utility function to delete any existing data directory and create a clean directory to which TensorFlow will log data for TensorBoard to parse and display.

StaggeredCallbackA simple child class of

tf.keras.callbacks.Callbackwith state andshould_runmethod to allow child classes to perform staggered execution of their event handlers.

EvaluateCallbackA child class of

StaggeredCallbackto invoketf.keras.Sequential.evaluateon our model instance every n completed epochs, writing out losses and metrics to the data log directory.

FilterRenderCallbackA child class of

StaggeredCallbackto render out the convolutional filters of a specified list of layer names every n completed epochs, logging the images to the data log directory.

The following code completes our example and performs the following tasks.

Create a TensorBoard log directory.

Configure IPU devices.

Create a model.

Create the datasets.

Define a list of metrics.

Compile the model.

Setup pipelining options.

Setup callbacks (note the use of our

FilterRenderCallbackandEvaluateCallbackclasses).Start the training session.

from tensorflow.python import ipu

# Setup log path.

log_path = create_tensorboard_log_dir()

# Configure the IPU device.

config = ipu.config.IPUConfig()

config.auto_select_ipus = 2

config.configure_ipu_system()

# Create a strategy for execution on the IPU.

strategy = ipu.ipu_strategy.IPUStrategy()

with strategy.scope():

# Create a Keras model inside the strategy.

m = create_model()

training_dataset, validation_dataset, test_dataset = create_datasets()

# Metrics.

metrics = [

"accuracy",

tf.keras.metrics.AUC(),

tf.keras.metrics.TopKCategoricalAccuracy(3),

]

# Compile the model for training.

m.compile(

loss=tf.keras.losses.CategoricalCrossentropy(),

optimizer=tf.keras.optimizers.RMSprop(),

metrics=metrics,

steps_per_execution=128,

)

# Setup pipelining.

m.set_pipelining_options(gradient_accumulation_steps_per_replica=16)

m.set_pipeline_stage_assignment([0] * 4 + [1] * 5)

# Trigger callbacks every step (default behaviour is every steps_per_epoch steps).

m.set_asynchronous_callbacks(True)

# Create callbacks for the training session.

callbacks = [

FilterRenderCallback(log_path, m, [f"conv_{n}" for n in [0, 1, 2]], 2),

EvaluateCallback(log_path, m, test_dataset, 5),

tf.keras.callbacks.TensorBoard(log_path, histogram_freq=1),

]

# Train.

m.fit(

training_dataset,

epochs=50,

steps_per_epoch=128,

validation_data=validation_dataset,

validation_freq=2,

validation_steps=128,

callbacks=callbacks,

verbose=False,

)

INFO:tensorflow:Training is and accumulating 16 batches per optimizer step, your effective batch size is 512.

WARNING:tensorflow:Callback method `on_train_batch_end` is slow compared to the batch time (batch time: 0.0002s vs `on_train_batch_end` time: 0.0132s). Check your callbacks.

WARNING:tensorflow:offload_weight_update_variables will have no effect since this pipeline is in inference.

128/128 [==============================] - 3s 1ms/step - loss: 0.8498 - accuracy: 0.8125 - auc: 0.9883 - top_k_categorical_accuracy: 1.0000

128/128 [==============================] - 0s 841us/step - loss: 0.5837 - accuracy: 0.8438 - auc: 0.9848 - top_k_categorical_accuracy: 0.9375

128/128 [==============================] - 3s 642us/step - loss: 0.5994 - accuracy: 0.8438 - auc: 0.9803 - top_k_categorical_accuracy: 0.9375

128/128 [==============================] - 0s 631us/step - loss: 0.3755 - accuracy: 0.8438 - auc: 0.9939 - top_k_categorical_accuracy: 1.0000

128/128 [==============================] - 3s 620us/step - loss: 0.2998 - accuracy: 0.9062 - auc: 0.9952 - top_k_categorical_accuracy: 0.9688

128/128 [==============================] - 0s 963us/step - loss: 0.3344 - accuracy: 0.8750 - auc: 0.9944 - top_k_categorical_accuracy: 0.9688

128/128 [==============================] - 3s 602us/step - loss: 0.1431 - accuracy: 0.9688 - auc: 0.9992 - top_k_categorical_accuracy: 0.9688

128/128 [==============================] - 0s 556us/step - loss: 0.2213 - accuracy: 0.9375 - auc: 0.9982 - top_k_categorical_accuracy: 1.0000

128/128 [==============================] - 2s 742us/step - loss: 0.0543 - accuracy: 1.0000 - auc: 1.0000 - top_k_categorical_accuracy: 1.0000

128/128 [==============================] - 0s 627us/step - loss: 0.2011 - accuracy: 0.9375 - auc: 0.9975 - top_k_categorical_accuracy: 0.9688

All of the above setup and training code is standard IPU TensorFlow operation

and should be familiar to any user of

IPU TensorFlow.

However, special attention should be paid to the

set_asynchronous_callbacks(True) call on our model m. This call allows the

model to asynchronously trigger callbacks at the end of an epoch, versus

queueing up callbacks to be executed at the end of the models execution.

Exploring TensorBoard

At this point, we should have a wealth of information available to explore in TensorBoard. So, go back to the previously empty TensorBoard dashboard we saw at the beginning of the tutorial and refresh the page. You will notice that the top navigation bar has changed and appears as follows.

We shall now look at the information available to us on each of the categories visible on the left of the navigation bar.

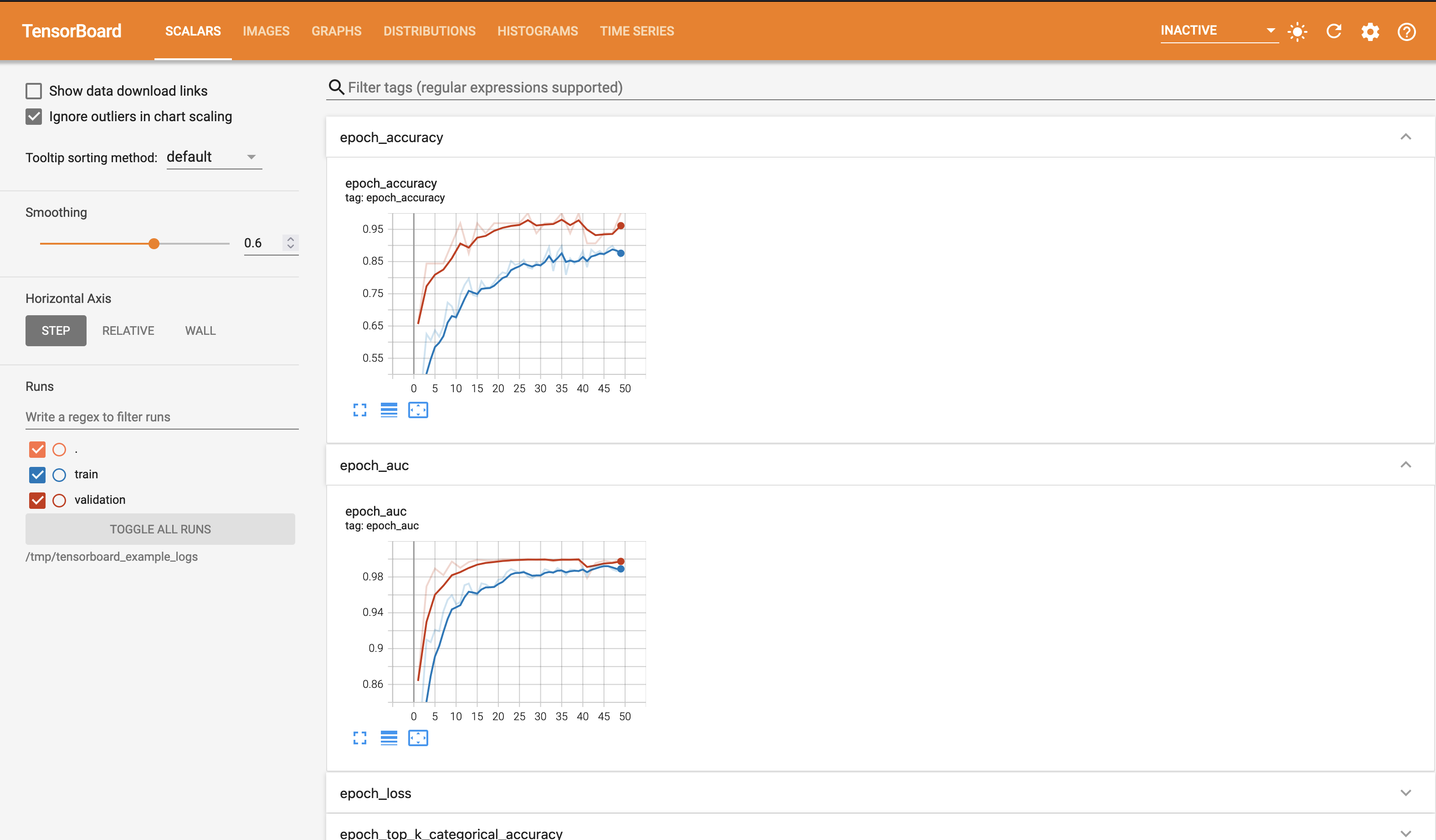

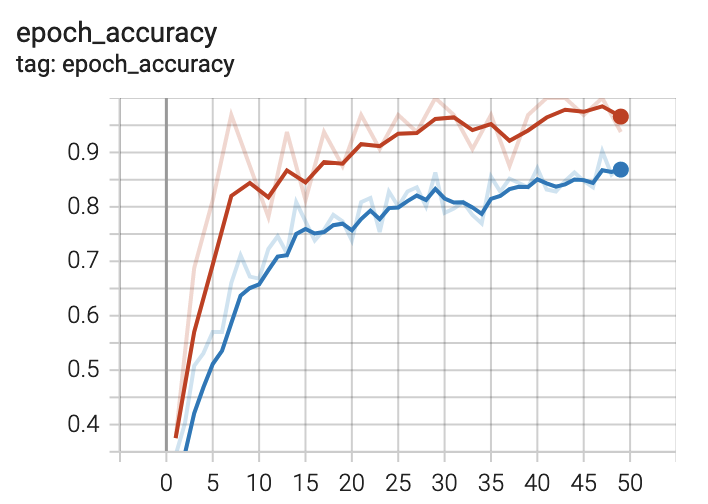

Scalars

The first and most immediately pertinent to training page we shall look at is

that for scalar data. Scalar data when written with a step provided is

plotted as a 2D graph (with step on the x axis). You should see a plot

similar to the following at the top of the page.

This is the training accuracy plot. Recall that we specified accuracy, AUC and

top-k ($k=3$) metrics for our model. There are two traces visible on the plot.

One is for training and the other for validation, recalling again that we

specified validation data in our call to fit. If you hover the cursor over

this plot, you will notice that the plot is interactive. Take a moment to play

with this.

You should also see the following training plots on this page.

epoch_auc

epoch_loss

epoch_top_k_categorical_accuracy

The training plots that you see on this page are the result of providing an

instance of tf.keras.callbacks.TensorBoard in our list of callbacks to fit.

The data logged for TensorBoard to generate these plots has been done so

automatically by this rather handy callback.

If we turn our attention to the remaining plots on this page, you should see something like the following.

In addition to evaluation_accuracy, you should see the following additional plots.

evaluation_auc

evaluation_loss

evaluation_top_k_categorical_accuracy

Unlike the training plots that were generated on data logged by our

tf.keras.callbacks.TensorBoard instance, these evaluation plots have been

generated by our custom EvaluationCallback class that we implemented earlier.

The first thing to notice about these plots is that they are far less smooth

than their training counterparts. This is not a bug! Recall that our custom

callbacks use staggered execution, so we are running an evaluation pass every

$n$ epochs, where in our case $n=5$ for our EvaluationCallback instance.

Perhaps as an exercise, you could play with different frequencies to find an optimum information quality/performance trade-off?

If performance isn’t a concern, perhaps the callback could be altered to compute a running mean over $n$ epochs? If not, take a moment to play with the smoothing coefficient in TensorBoard (slider to the left of the screen).

Images

We shall now turn our attention to the Images page in TensorBoard. When using

only the tf.keras.callbacks.TensorBoard callback, as will suffice in many

scenarios, there will be no images written out, so this page will not be

visible. However, recall that we have written our own callback

(FilterRenderCallback) to output images of our convolution layers filters.

There are many situations where one might wish to output image data to

TensorBoard during training, particularly in Computer Vision applications.

Semantic Segmentation for example would be one such application; one could

write out the original image with it’s segmentation masks applied.

If we look at the Images page now, you should see an image similar to the following.

Recall that every $n$ epochs (where $n=2$ in this case), the filters of our

three convolutional layers (conv_0, conv_1 and conv_2) are tiled and

rendered out by our FilterRenderCallback instance. As such, you should see

the following additional images on this page.

conv_1

conv_2

Take a minute to play with the brightness and contrast settings on the left of the screen. Does it help you to identify any kind of structure in the weights?

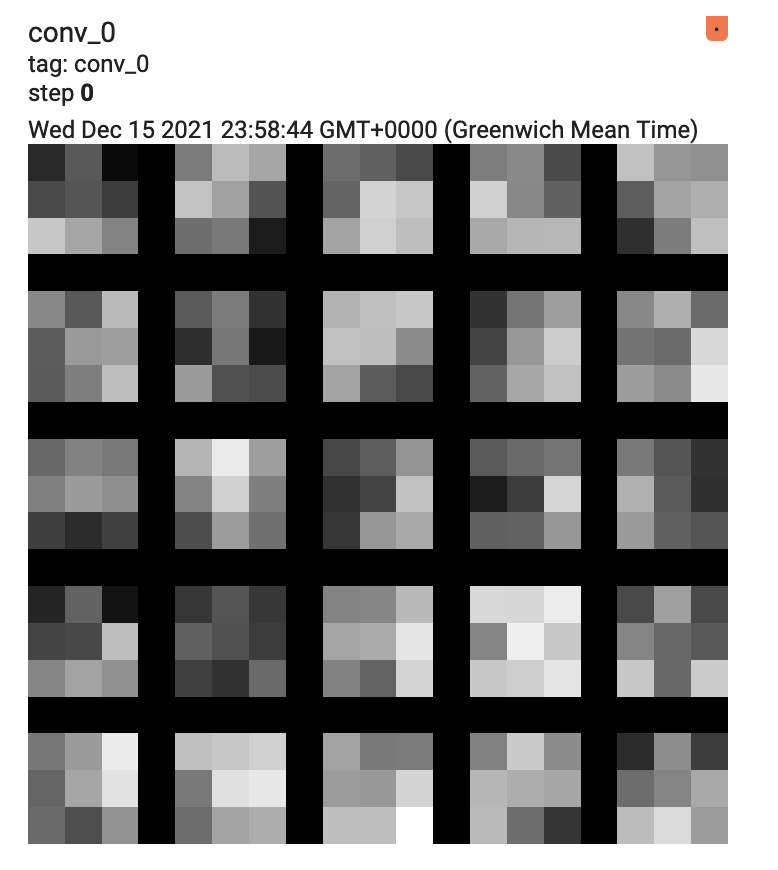

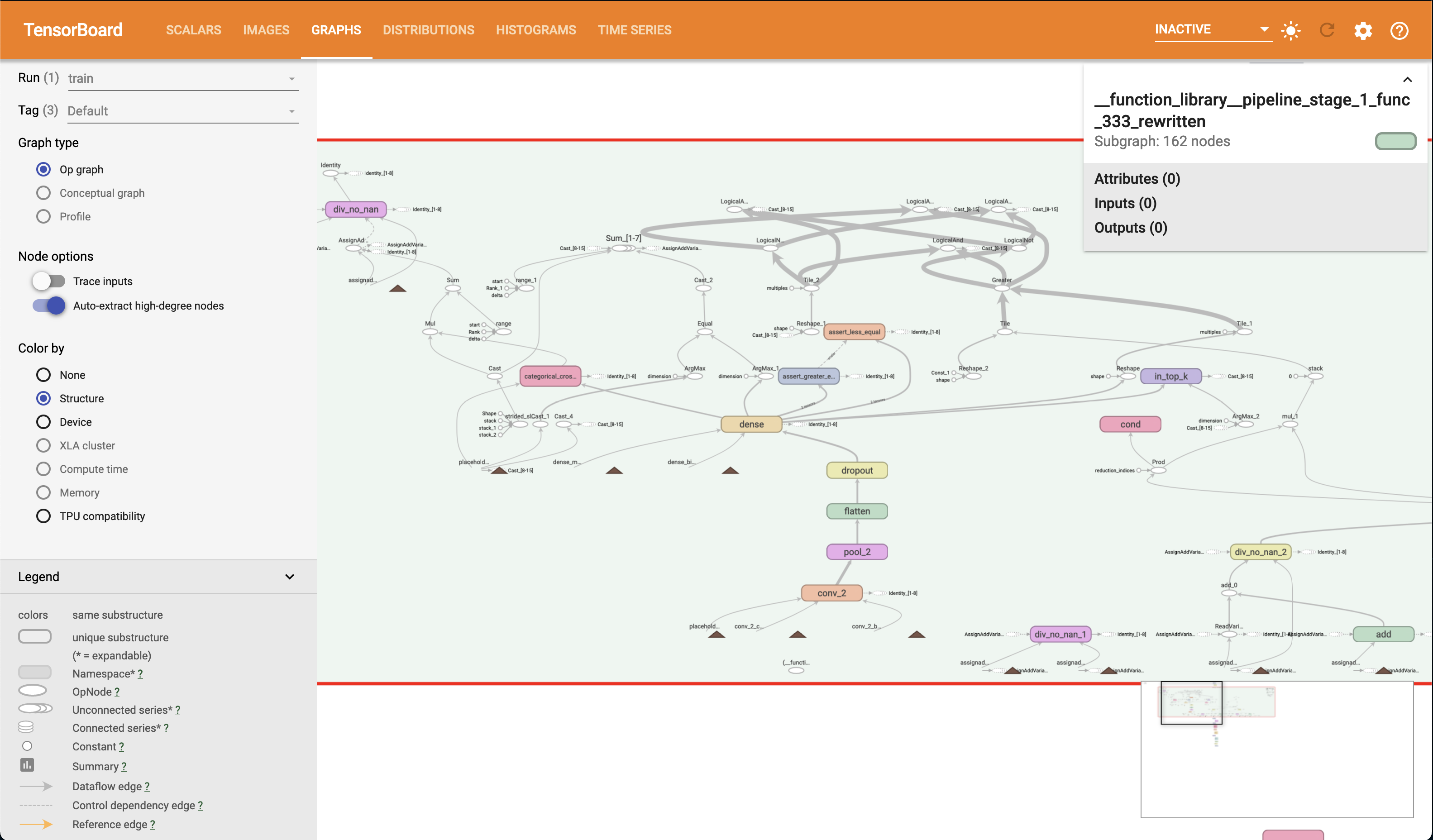

Graphs

The tf.keras.callbacks.TensorBoard callback provides a very useful data

output; the model graph. On this page, you will see some computation modules.

The Graphs page should look something like the following.

The Graphs page in TensorBoard provides an interactive graph explorer, in which modules and nodes can be expanded and collapsed, so it is very convenient to “drill down” into our model. For example, if we expand one of the pipeline stage modules (stage 1 in this case), you should see something like the following. Note that you can pan across the graph. Also note the view frustum indicator in the lower right hand corner of the screen.

As an exercise, can you identify the control dependencies that conv_2 has in the graph, using the graph exploration interface?

Perhaps it would be useful to take a few minutes to familiarise yourself with the Graphs page and it’s controls.

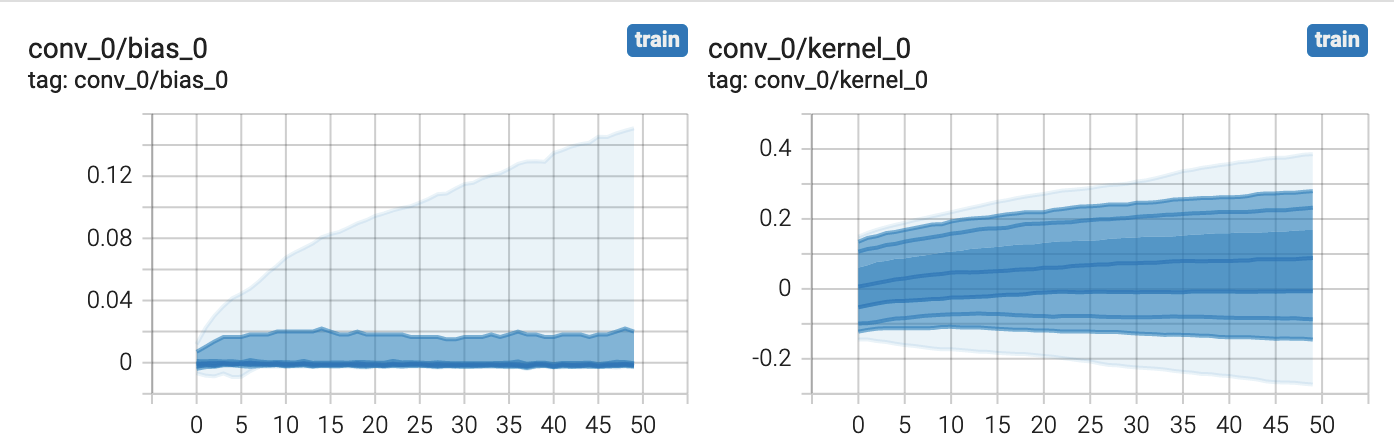

Distributions and Histograms

Distributions

The Distributions page in TensorBoard is another useful source of information

for inspecting your model. As with the model graph, the data displayed on the

Distributions page is generated by the tf.keras.callbacks.TensorBoard

callback we provided to our model. You should see two plots that look something

like the following.

The plots provided on the Distributions page provide statistical insight into

your models parameters. In the above example, we see how the distribution of

the weights and biases for our conv_0 layer changes over time. Each line in

the plot represents a percentile. The

TensorBoard Documentation

defines the percentiles as follows.

As Percentage |

As Standard Deviation |

|---|---|

Maximum |

Maximum |

$$ 93 % $$ |

$$ \mu + \frac{3 \sigma}{2} $$ |

$$ 84 % $$ |

$$ \mu + \sigma $$ |

$$ 69 % $$ |

$$ \mu + \frac{\sigma}{2} $$ |

$$ 50 % $$ |

$$ \mu $$ |

$$ 31 % $$ |

$$ \mu - \frac{\sigma}{2} $$ |

$$ 16 % $$ |

$$ \mu - \sigma $$ |

$$ 7 % $$ |

$$ \mu - \frac{3 \sigma}{2} $$ |

Minimum |

Minimum |

Take a moment to see how the plots displayed correspond to the above table.

This may be easier to do if you enlarge the plots (there is a button below each plot). It may be worthwhile doing this for each remaining parameter in our model, there should be plots for each remaining layer in our model.

conv_1

conv_2

dense

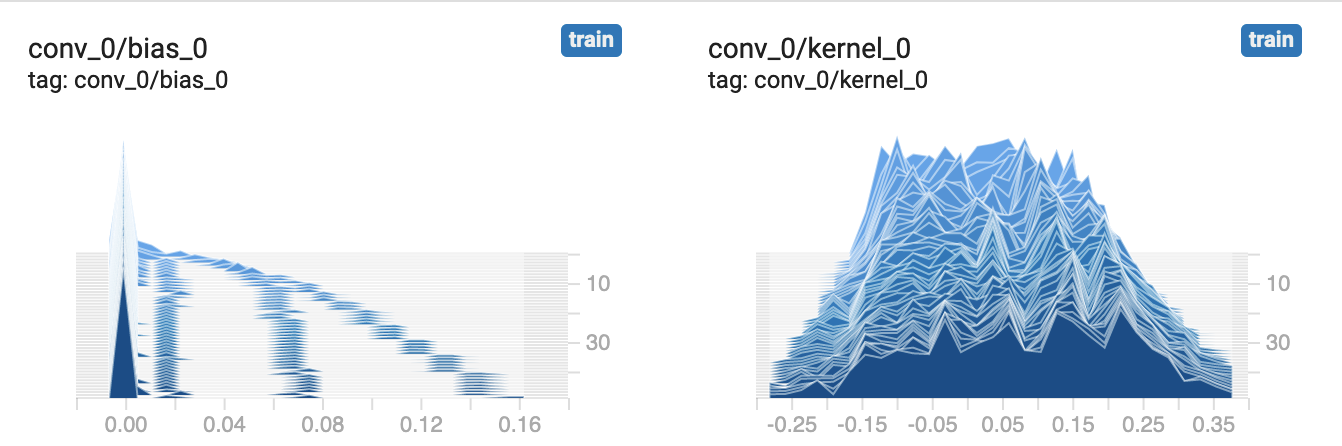

Histograms

The Histograms page provides an alternative view of the data presented in the

Distributions page. It is the same data, just presented differently. For

example, you should see two plots akin to the following, for our conv_0

layer.

As with the plots on the Distributions page, the plots on the Histograms page allow us to inspect the statistical properties of our models parameters. You will see that there are multiple histograms stacked for each parameter, indexed by time-step. Similarly to the Distributions page, we can also here see how our model parameters have evolved over time. Hover the cursor over one of the plots to see the outline for a given time-step.

Perhaps it would be useful to compare the data presented in these plots with those in the Distributions page? Do they correspond as one might expect?

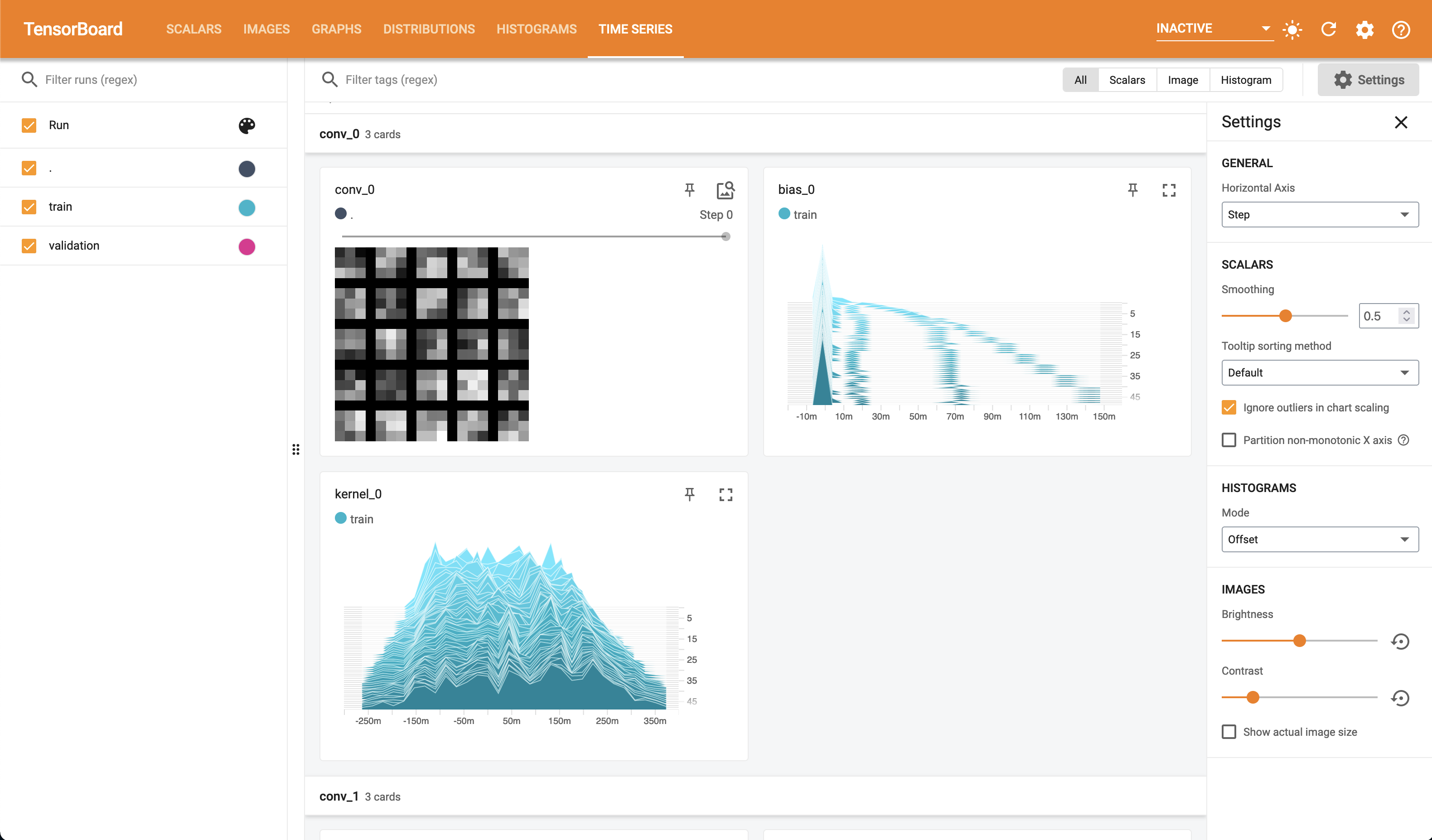

Time Series

The final page in TensorBoard that we will cover in this tutorial is the Time Series page. On this page you will see no new information or plots, however you will find all of the plots we have seen already in one place with controls to filter and move through time-steps. For example.

Using TensorBoard Without Keras

Although in this tutorial we have focused on the use of TensorBoard with Keras,

it is entirely possible to log data out to TensorBoard without using Keras and

tf.keras.callbacks.Callback instances. It just may involve some extra

implementation as we won’t have useful tools like

tf.keras.callbacks.TensorBoard. However, as we have seen, the actual logging

of data is achieved by the use of ops within tf.summary.

As an exercise, try to de-Keras-ify this model whilst keeping the same level of TensorBoard insight.

To Conclude

In conclusion, we have looked at TensorBoard and how it may be used with IPU

TensorFlow. We have covered primarily the case in which we are using Keras,

including how to write our own custom data logging callbacks via TensorFlow’s

summary ops (tf.summary). We have also seen the wealth of information

available to us by simply logging data using a built in callback

(tf.keras.callbacks.TensorBoard). Finally, we took a brief tour of the

TensorBoard interface and how to interpret some of the data presented to us

from the MNIST classifier we built for our experimentation.

Generated:2022-09-28T12:49 Source:demo.py SDK:3.0.0+1145 SST:0.0.8